CHES SMITH TRIO CHIME WITH VIGOUR AT THE VORTEX

July 11/2016

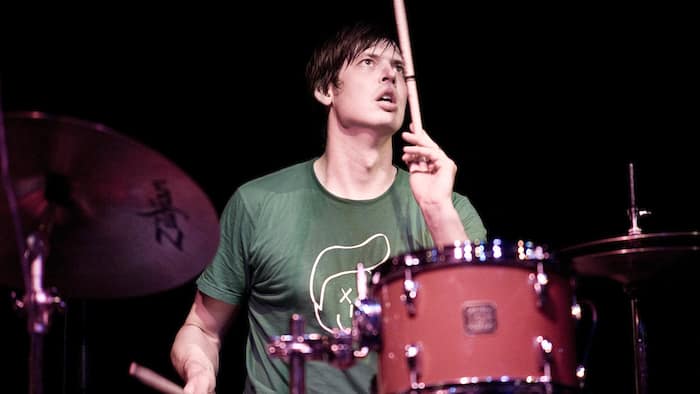

A tightly-packed bar area and the audible noise of the air conditioning says that this is a summer gig in east London that has drawn a crowd. Expectations are high given the release at the beginning of the year of Ches Smith’s excellent The Bell, but as the first sound of the evening –the glistening ripple of the vibraphone stationed next to his drum kit – is heard, there is an unvoiced but perhaps real discomfort in the ether. How will Smith, pianist Craig Taborn and viola player Mat Maneri rival the sound of the infernal machine that is supposed to stop players and punters alike making a live stream of their body salt? The simple answer is that over the course of two sets the musicians hit decibel levels high enough to make the whirring unit an irrelevance, torching it into silence by way of crash and burn grooves that have members of the audience rocking back and forth in their chairs, with no regard for breaking a sweat. Smith’s trio does loud as much as it does quiet.

These noise levels are important because they mark something of a departure from the general tenor of the recording, which for the most part has a softer resonance, though its appeal lies largely in the way the ensemble creates a kind of microcosmic intensity that goes beyond the standard vocabulary of ‘chamber jazz’. There is a use of space and pause that is part of the aesthetic common to all three musicians, as can be heard in previous collaborations between Maneri and Taborn for the Thirsty Ear label (2002’s gorgeous Sustain) and in Smith’s work with Tim Berne. But it soon becomes clear that, if there is tight control exerted on some of the structures, the improvisatory drive is not at all constrained and the explosive quality of much of the music easily fulfills the criteria of pop culture strands like rock, funk and hip hop.

The difference is that the vamps that arise organically from the passages of rubato have an altogether more lopsided character, sometimes rotating in 7/4 with the unerring consistency of a click track that doesn’t click quite as bloodlessly as when generated by a laptop. The machine sensibility, the absolute punch with which the players all hit the downbeat when they settle into a groove, is reinforced by the heaviness of the low end, something achieved partly by the interlocking of Smith’s kick drum and Taborn’s left-hand chords and partly by the range of effects created by Maneri’s pedals. His use of sub-bass as well as the buzzsaw quality of some of his rhythms, which vaguely evoke Leroy Jenkins, bulks up the sound, and as the performance unfolds there emerges a hardness in the ensemble character that is decidedly what might be expected from a band who could satisfy the raucous demands of a mosh pit as much as they could the more sedate setting of a seated concert hall. The sight of Smith pitch-bending his snare by placing his foot on the skin might be a thinly veiled encouragement to the crowd to loosen up.

Although the music stands out for its dynamism the tonal originality achieved by the group should not be overlooked. Smith is a drummer and vibraphonist whose shuttles between the two instruments enable him to create a melodic-rhythmic continuum full of shimmering colour as well as percussive detail, and this is enhanced by the variety of Taborn’s phrasing, above all his movement between prickly single note lines and sturdy ostinatos. The largely new material unveiled at this gig makes it clear that the recording of The Bell does not tell the whole story of Smith’s band, and that its careful harnessing of aggression amid attention to detail places it at an interesting juncture between jazz and electronica, between music that pushes out and music that kicks out over the competing noise of man-made gizmos, whether or not they are intended to reduce high temperatures in the middle of July.

– Kevin Le Gendre

JAZZWISE